October 16, 2004

ItŌĆÖs great white feeding time, again

by Peggy Townsend

PEGGY TOWNSEND - Sentinel staff writer

Article Launched: 10/16/2004 12:00:00 AM PDT

It was a cool, drizzly morning three weeks ago when Perry DiBenedetto and his surfing buddy Steve Shiner paddled out to the reef near Waddell Creek.

They are both longtime surfers, and as they bobbed in the gray-blue water, Shiner mentioned the place felt "spooky" that day. Not anything particular, just that little tingle in the spine; that little knot of worry that sometimes tightens in a surferŌĆÖs mind.

A minute later, a small elephant seal leaped out of the water. Then it leaped out again.

"I hope heŌĆÖs not being chased by a shark," the 49-year-old DiBenedetto said.

A few minutes later, DiBenedetto, a grounds supervisor at UC Santa Cruz, realized how right he had been.

For there, in the crest of the wave only 15 yards away, was an 8-inch high fin, and it was headed straight at him.

"Am I really seeing what I think IŌĆÖm seeing?" DiBenedetto thought.

Then he spotted a torpedo-shaped shadow in the ocean.

DiBenedetto had been around the ocean enough to believe it was a great white shark.

"Needless to say, we paddled so hard for shore ŌĆö we could have towed a water skier behind us," he says.

The shark followed them for a few feet, then disappeared.

It was the fourth report of a great white in Santa Cruz County that month.

In fact, some surfers call this time of year "Sharktober" because the huge sharks begin arriving about now at A├▒o Nuevo Island for their annual elephant-seal feed, and sightings become more common.

Almost half of all recorded shark attacks in Santa Cruz County San Mateo County to the north have been in September, October and November.

But thatŌĆÖs one of the few things researchers know ŌĆö or even agree on ŌĆö about the great white shark, a kind of Darth Vader of the deep.

The big predatorŌĆÖs life is one of the most mysterious on earth, says UC Santa Cruz biologist Burney Le Boeuf.

Researchers believe, for instance, that great whites feed around Central California in the fall, then head out to the mid-Pacific for a four- to six-month stay in winter.

But they donŌĆÖt know why they go there.

They know sharks have a keen sense of smell, and can pick up subtle electromagnetic fields, but they donŌĆÖt know exactly how often they have to eat.

They know that one shark fetus will kill and eat another shark fetus in the womb to survive ŌĆö but not where the sharks breed.

Still, most can agree on one thing:

"Anyone who is in the water on a regular basis on the North Coast, well, theyŌĆÖve been cruised," says Sean Van Sommeran of the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation.

South for winter Before 1999, researchers thought great whites lived only on the coast, traveling up and down like teenagers at a mall.

But in 1999 and 2000, local researchers managed to attach pop-up satellite tags to six great whites at A├▒o Nuevo and the Farallons during autumn. They tracked four of them as the animals hunted seals for six weeks, then in December, the sharks headed out to sea.

Three of them hung out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, halfway between Baja and Hawaii, while one ŌĆö a male ŌĆö went all the way to Maui (it took him 40 days to get there), according to Le Boeuf.

The sharks stayed four to six months, but researchers are not sure why.

It wasnŌĆÖt for food.

According to Le Boeuf, elephant seals, one of the great whiteŌĆÖs favorite foods, migrate north.

The sharks went south.

Then in October, the great whites start showing up again on the Central Coast, in an area called the Red Triangle, roughly from Point Reyes to the Farallons to A├▒o Nuevo.

They come to feed, Le Boeuf believes, after giving birth.

"But what we donŌĆÖt know and, what I canŌĆÖt tell you for a fact, is that sharks arenŌĆÖt here during the rest of the year," Le Boeuf says.

Experts can agree though: Your chances of running into a shark get higher in fall and early winter if you hang out in water thatŌĆÖs near a seal rookery like A├▒o Nuevo.

But humans arenŌĆÖt a sharkŌĆÖs preferred prey. Great whites are curious animals and it seems more likely bites are just their way of figuring out what a surfer in a wetsuit really is.

Sharks bite crab pots and tires. Once, Le Boeuf saw a female great white check out a plywood decoy that had been set in the water near A├▒o Nuevo Island.

"She lifted the decoy out of the water, then let it drift back out of her mouth and swam away," Le Boeuf says. "We couldnŌĆÖt find any distinguishing marks on the decoy" to show sheŌĆÖd even bitten down.

In fact, more injuries may occur when a victim yanks his or her arm or leg out of a sharkŌĆÖs razor-sharp teeth, rather than because the beast wants a human snack, Le Boeuf says.

Still, itŌĆÖs hard to stay calm in the face of a species that can grow to be 20 feet long and weigh as much as the combined weight of two college football teams ŌĆö 22 big, burly guys.

"They (great whites) remind me of that scene in the first ŌĆśStar WarsŌĆÖ when the Star Destroyer passes overhead," says Le Boeuf, who has witnessed them pass by the boat he was on.

"They seem to go on forever. They looks like theyŌĆÖre never going to go by."

In the bay Great whites donŌĆÖt appear just on the North Coast.

In 1960, a teen-age girlŌĆÖs leg was amputated after it was bitten by a shark at Hidden Beach in Aptos and Alex Peabody, the stateŌĆÖs chief aquatics safety officer, remembers a close call on a crowded New Brighton Beach on a July 4 weekend in 1997.

Peabody was on a lifeguard boat when he spotted the great white that day. He called for other lifeguards to clear the beach, then turned the boat to rescue a couple of long-distance swimmers in the water nearby.

The woman swimmer scrambled into the boat when she was told about the shark, but her husband was a different story.

"He said, ŌĆśIŌĆÖll be fine. IŌĆÖll just head right in,ŌĆÖ " Peabody remembers.

"HeŌĆÖs always like that," the wife said.

"IŌĆÖm like, ŌĆśOh my God, this guy wonŌĆÖt come in,ŌĆÖ " Peabody says and remembers how the shark turned and headed for the stubborn swimmer.

Peabody accelerated the boat forward, then threw it into reverse, putting it between the swimmer and the 12-foot great white.

Peabody yelled, "Get in the boat right now," as his deckhand grabbed the swimmerŌĆÖs wetsuit and hauled him onboard.

Seconds later, the shark glided under the boat to the spot where the man had been.

"The guy looked over and said, ŌĆśOh, thatŌĆÖs a big fella isnŌĆÖt itŌĆÖ?" Peabody remembered

"His wife said, ŌĆśHeŌĆÖs always like that.ŌĆÖ "

Blue ambush Sharks are warm-blooded animals, which is why they ambush their prey, according to Dave Casper, campus veterinarian at UCSC and part of the crew who did shark research in the late ŌĆÖ90s.

Being warm-blooded in a cold ocean is "incredibly expensive" in terms of energy, he says. So instead of using energy to chase its meal, the shark will glide along the bottom until it senses something on the surface.

Then, it will strike.

Sean Van Sommeran, a self-taught shark researcher who has spent years studying the great white, describes the violence of an attack:

The shark, he says, will flick its powerful tail and swim upward about 30 mph, hitting its prey like a mortar shell and then giving it a huge shake, which is strong enough to tear an elephant seal in half.

But sharks arenŌĆÖt born that way ŌĆö even though they may eat each other in the womb.

When they are young, they eat fish.

It is only when they reach about 14 feet that they start eating fat seals and sea lions, Casper says.

"Most human attacks I regard more as nudges and bites than attacks," Van Sommeran says.

Great white sightings may come when an animal rises to the surface to use its keen sense of smell to locate a seal that got away, Van Sommeran says.

Or, it may be listening on the surface for the animal the same way trackers listened for hoofbeats by putting their ear to the ground.

These ancient, piscine hunters also have the ability to sense subtle electromagnetic fields that may help locate prey.

"They are often fascinated by the static electricity from a boat propeller and will come up and give it a nudge," Le Boeuf says.

But whatever a great white is doing on the surface, itŌĆÖs time to get out of the water if one is around.

And it may be that humans are more threatening to great whites than the other way around.

No one knows the size of the great white population, but like other apex predators, it is probably small.

And numbers may be dwindling.

There is a big international market for shark fins, which can sell for $3,000 each, and for shark skulls, which can bring in $10,000 or more, Van Sommeran says.

This week, the U.N.-affiliated Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species met in Thailand and called for stepped-up protection of great whites as a threatened species, according to a National Public Radio report.

Back in the water Many local surfers, divers and kayakers deal with sharks the easy way ŌĆö by not thinking about them.

"Denial is my favorite therapy," says Rand Launer, 58-year-old surfer-carpenter-kayaker who came across what might have been a great white off Woodrow Avenue during a paddle last month.

They say they have a greater chance of being killed some other way ŌĆö and they would be right.

The odds of being killed by a shark is 1 in 300 million.

The odds of dying from food poisoning is 1 in 3 million.

But talk to North Coast surfers and many will say theyŌĆÖve had those spooky moments: the seal that is swimming erratically near them, the sudden boil of water.

Many of them ŌĆö even those who surf the monster waves of MaverickŌĆÖs in Half Moon Bay ŌĆö will simply get out of the water.

"IŌĆÖve never seen a great white, not even a fin," professional big wave rider Peter Mel says.

But once, at a place called Horsehoes north of Scott Creek, he had two harbor seals leap over his board.

"Like flying fish," he says.

Mel had heard that a great white had been spotted there the day before and a surfer had been attacked there in 1999.

He paddled in.

Five attacks have been reported on the West Coast this year, according to Ralph Collier of the Shark Research Committee, which keeps a running log of reported shark sightings.

Earlier this month, a shark took a bite out of a 16-year-oldŌĆÖs board near Pismo Pier. This week, a shark grabbed a surferŌĆÖs leg at Point Reyes.

There also have been a number of local sightings.

In September, three "credible" sightings of great whites were reported off Manresa State Beach, according to Collier.

But the great white that is probably being seen most often is the young shark captured off Southern California that is now in the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Thousands have flocked to see it.

Santa Cruz County isnŌĆÖt the sharkiest place in California, according to the state Department of Fish and Game. There have been five attacks here since record-keeping began. Marin County has had 12; San Mateo County 11.

And if you thought you were safe because you donŌĆÖt free-dive or surf ŌĆö the activities that have resulted in the most attacks ŌĆö think again.

Three waders have been bitten by sharks in California, including an unidentified beach-goer at Pajaro Dunes in 1978.

And in 1990, a shark came into the surf line at Manresa and followed a boogie boarder right up to the beach, according to lifeguard Peabody.

"That was kind of exciting," he says.

But peopleŌĆÖs fear of being killed by a great white may be more of a "media sensation" than anything else, says Gary Strachan, a supervising ranger for North Coast state parks who is also a surfer and kite-boarder.

Lots of things are more likely to happen than a shark attack, he says.

"At Waddell, a Rottweiler attacked a guy and bit through his hand," says Strachan, who had his own close encounter with a great white at Waddell reef three years ago. "I didnŌĆÖt see any big hype on that."

"ThereŌĆÖs always a certain amount of danger associated with surfing up north," surfer DiBenedetto says, "but I surf the North Coast breaks because I have less tolerance and patience for the crowded conditions in town."

Or increasingly aggressive surfers.

"IŌĆÖd rather risk an encounter with a great white shark," he says, "than an aggressive, hostile surfer in the water any day."

Contact Peggy Townsend at ptownsend@santacruzsentinel.com.

Shark attacks by activity Free-diving .... 27

Surfing .......... 23

Swimming ..... 12

Scuba diving .. 12

Commercial diving .............. 8

Kayaking ......... 5

Wading ........... 3

Windsurfing ..... 1

Long boarding ... 1

Scooter ............ 1

Total: 93

Source: state Department of Fish and Game

Shark attacks in Santa Cruz County May 19, 1960: Swimmer at Hidden Beach, Aptos

Aug. 8, 1978: Wader at Pajaro Dunes

July 1, 1991: Surfer in Davenport

Oct. 5, 1991: Surfer, one mile north of Scott Creek

Sept. 9, 1995: Windsurfer, Davenport Landing

Source: state Department of Fish and Game

By Peggy Townsend

Original URL (may no longer function):

http://www.scsextra.com/story.php?sid=73519

Copyright © Santa Cruz Sentinel. All rights reserved.

|

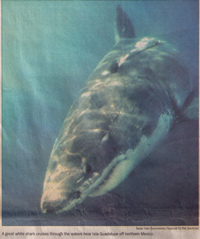

A great white shark cruises through the waters near Isla Guadalupe off northern Mexico (Sean Van Sommeran / Special to the Sentinel)

Sc Sentinel Front Page Scan

|