Alessandro De Maddalena

Wrongly maligned as man-eating monsters, sharks seldom attack humans,

but their populations are being rapidly depleted by overfishing and

other human activities.

ention the word sharks, and what goes ention the word sharks, and what goes

|  The

great white shark is one of the few shark species known to attack

humans. This 17-foot specimen was caught in a tuna trap off the coast

of Tunisia. Populations of this species have been depleted by

intentional and accidental catches, and some countries have listed it

as endangered. WALID MAAMOURI The

great white shark is one of the few shark species known to attack

humans. This 17-foot specimen was caught in a tuna trap off the coast

of Tunisia. Populations of this species have been depleted by

intentional and accidental catches, and some countries have listed it

as endangered. WALID MAAMOURI

through your mind? The movie Jaws? Ferocious giants of the sea ripping

up helpless swimmers, surfers, and boaters? The word is even applied to

people who engage in extortion, preying on others through deceptive

practices.

Yes, sharks are

predators that occupy the top layer of the marine food web, and many

are large and powerful enough to be capable of harming a person. Even

so, only certain species pose a definite danger to people who venture

into their habitat, while most are inoffensive. On a worldwide scale,

the number of shark attacks on humans amounts to about 100 per year, of

which only 5 to 15 are fatal. In most cases, the attack ends after the

initial contact and the shark does not kill or eat the victim.

By comparison,

many more people die each year from water-related activities that do

not involve sharks. Even the number of casualties from lightning

strikes is much higher. Unfortunately, each shark attack is

sensationalized by the media, and these stories then shape public

perception of sharks.

On the other hand,

human activities exert a key influence on shark survival. In recent

years, as fisheries relying on other types of fish have declined, shark

captures--both intentional and accidental--have greatly increased.

According to an estimate reported online by NOAA Fisheries, over 100

million sharks are killed each year. Consequently, populations of many

species have been dramatically reduced.

To gain a better

perspective on these conflicting issues, it is important to understand

sharks in terms of their biological features, life cycles, dietary

habits, and role in marine ecosystems. In addition, we need to consider

how they are affected by commercial and recreational fishing.

Characteristics of sharks

harks can be

found in all the world's seas, from the equator to the polar regions,

in shallow as well as deep waters. We are currently aware of about 480

species of sharks, occurring in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some

species, labeled benthic, dwell mainly on the seafloor. Others, known

as pelagic, spend much of their time navigating the open seas, although

they may also be found on the ocean bottom. Some species inhabit rivers

and lakes. harks can be

found in all the world's seas, from the equator to the polar regions,

in shallow as well as deep waters. We are currently aware of about 480

species of sharks, occurring in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some

species, labeled benthic, dwell mainly on the seafloor. Others, known

as pelagic, spend much of their time navigating the open seas, although

they may also be found on the ocean bottom. Some species inhabit rivers

and lakes.

One important

distinguishing feature of sharks is that their skeletons are made of

cartilage, while those of most other types of fish are made of bone.

Other cartilaginous marine animals include rays, skates, and chimaeras,

and they--as well as sharks--are grouped in the class Chondrichthyes.

Bony fishes, on the other hand, are placed in the class Osteichthyes.

Generally

speaking, a shark has a streamlined body with a long, flattened snout,

a parabolic mouth on the ventral (lower) side, and eight fins: two

pectoral and two pelvic fins, and one each of the first dorsal, second

dorsal, anal, and caudal (tail) fins. The upper lobe of the caudal fin

is noticeably longer than the lower one. Furthermore, the male's pelvic

fins are extended to form a pair of organs called claspers, which are

used to impregnate females.

The body shape,

however, varies according to the way of life of the species. For

example, fast-swimming mackerel sharks have a large, conico-cylindrical

shape; benthic cat sharks have long, slender bodies; and benthic angel

sharks and saw sharks are highly flattened in shape. Hammerhead sharks

have unique, rectangular heads.

Minimizing the Risk of Shark Attacks

Shark attacks on

humans are rare, with encounters occurring mainly near the shore.

Sharks are often found inshore of a sandbar or between sandbars, where

they may be trapped during low tide, and near steep drop-offs, where

their prey tend to congregate. To minimize the risk of being attacked

by a shark, it is important to take the following precautions.

When swimming at a beach, stay in a group and do not go too far from the shore.

Avoid being in the water during the hours of twilight, early morning, and darkness, when sharks are most active.

Stay out of the water if you are bleeding.

Do not enter the water wearing shiny jewelry or bright clothing.

Avoid areas being used by fishermen, especially if you see diving birds or other signs of bait fishes and feeding activity.

Exercise caution when entering murky waters and areas near sandbars or steep drop-offs.

Do not enter the water if sharks are known to be present, and evacuate the water if you see a shark.

Condensed from

information provided by NOAA Fisheries at

www.mfs.oaa.gov/sharks/Press--Kit--Sharks.htm and the Florida Museum of

Natural History at

www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Sharks/Attacks/relariskreduce.htm. |

The world's largest

fish is the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), which may reach 65 feet in

length. The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) can attain a

maximum length of more than 20 feet [see "Marine Predator

Extraordinaire," The World & I, November 1994, p. 218]. Most shark

species, however, are under 5 feet. The smallest of them is the dwarf

lanternshark (Etmopterus perryi), only about 6 inches at maturity.

Sharks differ from

bony fishes in several ways, in addition to the differences in skeletal

composition. For instance, most bony fishes have a swim bladder in

their upper body cavity. It is a gas-filled sac that lends buoyancy by

offsetting the weight of bony tissue. Sharks lack this bladder, but

they are only slightly heavier than seawater because of their light,

cartilaginous skeleton and huge, oily liver. Moreover, the gills of

bony fishes are covered by a flap called an operculum, while sharks'

gill slits are uncovered.

A shark's skin is

covered by small (usually microscopic) toothed structures known as

dermal denticles or placoid scales, which help reduce friction while

swimming. These structures generally point toward the tail (though in

some cases they are vertically oriented), so that rubbing the skin from

tail to head gives a sandpapery feeling.

A shark's mouth

contains 5 to 15 parallel layers of teeth so that when the front teeth

break off, as happens frequently, new ones quickly take their place.

Depending on the species, a shark may shed 10,000 to 50,000 teeth in

its lifetime. The teeth vary in shape, according to the animal's diet.

For instance, the great white shark has sharp, wide teeth, suitable for

shearing or sawing pieces from large animals. The shortfin mako (Isurus

oxyrinchus) has narrow, curved teeth adapted for seizing smaller,

fast-moving schools of fish. The common smooth hound (Mustelus

mustelus) has smooth, flattened teeth that enable it to crush hard prey

such as mollusks and crustaceans.

Sharks have a

highly developed nervous system, with several types of senses that are

mainly used to find and catch prey. These senses include (1) smell and

taste (chemoreception); (2) vision (photoreception); (3) hearing,

touch, and a lateral line system (mechanoreception); and (4) ampullae

of Lorenzini (electroreception). The lateral line system--consisting of

a series of sensory canals just beneath the skin, running lengthwise on

each side of the body--enables the animal to detect vibrations and

changes of pressure in the water. The ampullae of Lorenzini are

receptors (on the shark's head) that can detect weak electric fields,

such as those produced by the muscular contractions of prey.

Reproduction and feeding

ompared with

other types of fish, sharks have a slow growth rate. As a result, their

sexual maturation takes a long time--from 2 to 20 years, depending on

the species. In addition, they produce relatively small numbers of

young--the litter size usually ranges from 2 to 20. In many cases,

litters are produced only every alternate year. ompared with

other types of fish, sharks have a slow growth rate. As a result, their

sexual maturation takes a long time--from 2 to 20 years, depending on

the species. In addition, they produce relatively small numbers of

young--the litter size usually ranges from 2 to 20. In many cases,

litters are produced only every alternate year.

|  A

nurse shark is normally inoffensive to humans unless provoked. Its

flattened body helps it hide on the seafloor where it dwells. A

nurse shark is normally inoffensive to humans unless provoked. Its

flattened body helps it hide on the seafloor where it dwells.

COREL STOCK PHOTO

The reproductive

methods used by sharks may be classified into three types, in each of

which the eggs are fertilized within the female. In one group of

species, described as oviparous, the females lay horny egg cases, each

containing an embryo nourished by a yolk sac. The females of a second

group, termed aplacental viviparous, give birth to live young that were

sustained in the uterus by a yolk sac. In a third category, called

placental viviparous, the females produce live young that were nurtured

by placenta in the uterus.

The average

gestation period is 9--12 months, but it takes up to 22 months for the

piked dogfish (Squalus acanthias). When the pups are born, they are

fully formed and ready to feed. The maximum life span of a shark ranges

from 10 to 70 years or more, but members of most species live 20--30

years.

The diverse

species of sharks specialize in pursuing specific groups of prey, but

humans are not on the menu of any species. Some of the giant

species--namely, the whale shark, basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus),

and megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios)--are content to feed on

planktonic organisms, including small crustaceans, fish eggs, and fish

larvae. The diet of other species includes other types of fish,

mollusks, crustaceans, worms, echinoderms (sea stars and sea urchins),

pinnipeds (seals and sea lions), cetaceans (whales and dolphins),

marine turtles, sea snakes, and seabirds. Most sharks feed mainly on

live prey, but some are scavengers, feeding on dead animals.

Given the large

size of most sharks, they themselves are excluded from predation by

most other animals. Their eggs and young, however, are susceptible to

certain types of fishes and mollusks. In addition, adult sharks are

eaten by a few species, including humans, other sharks, some bony

fishes such as large groupers, and a few marine mammals such as the

killer whale and sperm whale.

As predators and

scavengers, sharks play an important ecological role in marine

communities. From their position as apex predators, they exert

substantial control over the sizes of the populations of many species

on lower levels of the food web. Consequently, they contribute to the

stability of marine ecosystems and maintain biodiversity.

Attacks on humans

hile sharks do

not normally pursue humans as prey, some people are occasionally

attacked by certain species. The three species responsible for most

attacks are the great white shark, tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), and

bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas). hile sharks do

not normally pursue humans as prey, some people are occasionally

attacked by certain species. The three species responsible for most

attacks are the great white shark, tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), and

bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas).

Equipped with wide

mouths and big, serrated teeth, these powerful creatures normally feed

on large prey. In addition, they are widely distributed in the seas of

the world. Sometimes they have been aggressive toward  |  The

author displays the jaws of an 18-foot great white shark caught off

Martigues, France. The jaws are preserved at the Oceanographic Museum

of Monaco. ALESSANDRA BALDI / PERMISSION FROM MUSÉE OCÉANOGRAPHIQUE DE MONACO The

author displays the jaws of an 18-foot great white shark caught off

Martigues, France. The jaws are preserved at the Oceanographic Museum

of Monaco. ALESSANDRA BALDI / PERMISSION FROM MUSÉE OCÉANOGRAPHIQUE DE MONACO

humans without apparent provocation, but there have been many reports of these animals

approaching divers and bathers closely without showing any aggressive tendencies.

Other species that

have occasionally harmed humans are the blue shark (Prionace glauca),

shortfin mako, great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokarran), oceanic

whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus), lemon shark (Negaprion

brevirostris), dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus), gray reef shark

(Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos), bronze whaler shark (Carcharhinus

brachyurus), blacktip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus), and

blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus).

The attacks may

occur in water that is shallow or deep, warm or cold, but most have

been recorded in areas favorable for recreational swimming,

particularly in Florida. Not only is Florida's coastline popular with

swimmers and surfers, but many potentially dangerous sharks inhabit

those waters.

What motivates a

shark to bite a human? It appears that in most cases, the animal

mistakenly identifies the person as a marine mammal or other type of

prey. After taking a bite, it discovers its mistake and releases the

person without inflicting additional injury. Alternatively, the shark

may be using a defensive tactic, to protect itself from what it may

perceive to be a potential threat. Repeated attacks on a human victim

are rare. Whatever the case, it is important to take certain

precautions to minimize the risk of being bitten by a shark [see

"Minimizing the Risk of Shark Attacks" on p. 152].

Depletion of sharks

or centuries,

fishermen around the world relied on traditional methods to catch

sharks (as well as other types of fish), and shark populations remained

stable. Recently, however, several factors have led to serious

depletion of shark populations. or centuries,

fishermen around the world relied on traditional methods to catch

sharks (as well as other types of fish), and shark populations remained

stable. Recently, however, several factors have led to serious

depletion of shark populations.

One problem is

that large-scale fishing methods have substantially reduced stocks of

bony fishes, and commercial fishermen have compensated by vastly

increasing the capture of sharks. Today, most shark species are being

overfished in many seas of the world. Many species yield marketable

products--namely, their meat, cartilage, skin, and oil. Shark meat is

consumed in almost all Atlantic and Mediterranean countries, where it

is traded fresh, chilled, frozen, and dried.

Moreover, an

estimated 50 percent of the sharks captured worldwide are part of what

is called the bycatch--that is, the fish caught accidentally, while

attempting to catch other species. A major factor contributing to this

problem is the use of gear known as pelagic longlines, generally

employed to catch swordfish and tuna. This gear consists of

single-stranded fishing lines, each stretching anywhere from 10 to 40

miles, carrying an average of 1,500 baited hooks. In some areas, the

number of sharks caught accidentally in longlines reaches 90 percent of

total captures. Species such as the blue shark and shortfin mako are

especially vulnerable to this method.

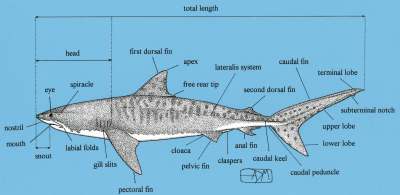

|  Exterior

anatomy of a tiger shark. The spiracle, a small opening behind each

eye, functions with the gills to absorb oxygen from the water. The

lateralis system consists of sensory tubes (under the skin) that help

the animal detect vibrations and pressure changes in the water. The

claspers, occurring only on the male, are used to impregnate the

female. ALESSANDRO DE MADDALENA Exterior

anatomy of a tiger shark. The spiracle, a small opening behind each

eye, functions with the gills to absorb oxygen from the water. The

lateralis system consists of sensory tubes (under the skin) that help

the animal detect vibrations and pressure changes in the water. The

claspers, occurring only on the male, are used to impregnate the

female. ALESSANDRO DE MADDALENA

Another problem is

that large numbers of sharks are killed and wasted through the practice

of finning them at sea. Shark fins are often used in Asian soups, and

their market value is much higher than that of other shark products.

Consequently, some fishermen remove the fins and discard the rest of

the shark's body into the sea. This practice has recently been banned

by Canada, Brazil, the United States, and the European Union.

Several shark

species are caught by recreational anglers, many of whom consider even

young sharks to be "large fishes." The population of blue sharks in the

Adriatic Sea has been devastated by years of unmonitored, unregulated

sportfishing in their nursery area. Thresher sharks (Alopias species)

have also been greatly affected by sportfishing.

Furthermore, shark

populations are being adversely affected by human activities that are

less direct but just as harmful. One such factor is overfishing of

their prey, such as tunas, mackerels, pilchards, rays, squids, and

crustaceans. Other indirect factors include environmental pollution and

habitat destruction. If certain toxic chemicals are ingested by

animals, they accumulate in each individual and are passed up the food

web, from prey to predator. Consequently, apex predators such as sharks

are at higher risk of receiving concentrated toxins from their prey.

Mediterranean Shark Research Group

The Mediterranean

Shark Research Group (MSRG) was initiated in the summer of 2000 by some

researchers at the Marine Biological Station of Piran (in Slovenia),

the Barcelona Museum of Zoology, and the Italian Great White Shark Data

Bank. Their purpose was to establish and expand an information exchange

network among ichthyologists studying sharks of the Mediterranean, in a

spirit of mutual collaboration. Today, the group includes 30

researchers from 10 countries and has launched several projects,

including studies on shark capture in the Mediterranean by

sportfishermen and the occurrence of shortfin makos along Italian

coasts. It is also investigating the age and growth of the basking

shark in collaboration with the Natal Sharks Board of South Africa.

The MSRG programs

are cause for optimism, as they indicate that some positive changes are

finally occurring. The group, however, faces serious difficulties

because the corresponding national governments display little interest

in these projects. The MSRG alone, with its members working on a

voluntary basis, will not ensure the conservation of Mediterranean

shark populations. The governments of major European shark-fishing

countries should put far more resources into research on shark biology

and fisheries, and the European Union must finally assume an important

role in shark conservation in both Atlantic and Mediterranean waters.

--A.D.M

|

Sharks are much

more vulnerable to overexploitation than bony fishes, for several

reasons. Their growth rate is slow, their sexual maturation and

gestation periods are long, and they produce small litters of young.

The exploitation of pups in a nursery area can be particularly

devastating for their population. By contrast, bony fishes lay numerous

eggs, and they grow and reproduce much faster. As a result, shark

populations recover from overexploitation far more slowly.

The problem of

overfishing of sharks is difficult to quantify. Annual landings of

cartilaginous fishes, as reported to the UN Food and Agriculture

Organization, amount to around 820,000 metric tons. The actual total,

however, is surely much higher because large quantities of catch are

not recorded. Every year, thousands of dead sharks are thrown back into

the sea for lack of demand in many countries.

The piked dogfish

is the leading commercial shark taken in the world. In the Atlantic

Ocean, species such as the porbeagle (Lamna nasus), shortfin mako,

piked dogfish, smooth hounds (Mustelus species), and requiem sharks

(family Carcharhinidae) are heavily exploited and their stocks have

dramatically declined. Species that have become sporadic or rare in the

Mediterranean Sea include the great white shark, shortfin mako,

porbeagle, sandtiger (Carcharias taurus), smooth hammerhead (Sphyrna

zygaena), sandbar shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus), bramble shark

(Echinorhinus brucus), and angular roughshark (Oxynotus centrina).

The decline of

shark populations warrants an urgent investigation into the status of

various species. To take effective conservation and management

measures, further research needs to be performed to determine specifics

about their life cycles, feeding habits, distribution, and exploitation

from various seas. The information obtained, coupled with long-term

analyses of their relative abundance, would offer insights into

restoring their populations. Of course, the protection of sharks also

requires protecting their prey and managing other fisheries in which

sharks constitute a significant bycatch.

The absence of

research and management efforts in many countries is leading to the

extinction of several species of sharks. In the Mediterranean area, no

country keeps accurate records of each species captured; and in the

entire Atlantic-Mediterranean region, only a few nations (particularly

the United States and Canada) have developed specific shark-management

programs. In some countries, certain species--such as the basking shark

and great white shark--are listed as protected. That, however, is not

enough; the list of endangered species is far from complete. Moreover,

fishermen often breach regulations and capture even the handful of

protected species.

Researchers in the

Mediterranean area are fully aware of this situation, but European

governments seem to lack interest in shark conservation. Shark research

is almost entirely neglected in favor of studying bony fishes, such as

tuna and swordfish, which are commercially important.

The threat to

shark populations is part of an immense problem confronting world

fisheries. Most seas have been fished to the limits of their

productivity. Advances in fishing technologies, along with rising

demands by a growing human population, have led to heightened efforts

to catch fish, mollusks, and crustaceans. As a result, the stability of

marine ecosystems is in serious danger. It is incumbent on us to devise

appropriate strategies to protect and restore the populations of these

sea creatures.

On the Internet

NOAA Fisheries Shark Web Site

www.mfs.oaa.gov/sharks

ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research

www.elasmo-research.org/index.html

Sharks: Florida Museum of Natural History

www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Sharks/sharks.htm

Alessandro De Maddalena is curator of the Italian Great White Shark

Data Bank and a founding member of the Mediterranean Shark Research

Group.

|