| |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

| |||||||||||

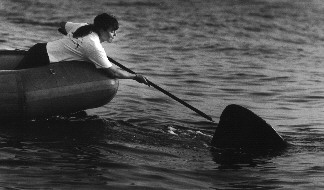

Basking Sharks - Cetorhinus maximusRESEARCH

Basking shark tagging efforts... DESCRIPTION The basking shark is recognized by its huge size, conical snout, sub-terminal mouth, extremely large gill slits, dark bristle-like gill rakers inside the gills (present most of the year), strong caudal keels on the caudal peduncle, and a lunate tail. Teeth are very small and numerous. Color is a mottled grayish brown to slate-gray or black above, sometimes with lighter patches, while the undersides are paler, often with white patches under the snout and mouth or along the ventral side. Two albino specimens from the North Atlantic have been recorded. It is the second largest fish, only surpassed by the whale shark in size. Average size is 22-29 ft. The largest measured specimen was 32 ft., and a 30 ft. individual was recorded to be 8, 600 lbs. There are unconfirmed reports of basking sharks up to 45ft. long. When first seen in the water, the basking shark's large size has sometimes caused it to be mistakenly identified as a great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) but this gentle giant is a planktivore. It opens its cavernous mouth (up to 4ft. Across!) to allow water to pass over the gill rakers, which then strain small fishes and invertebrates out of the water column. They are often seen feeding in this manner when near the surface. DISTRIBUTION Basking sharks are found in temperate waters of both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. They are usually observed by humans at or near the surface, and have been sighted along almost every coastline bordering both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Along the West coast of North America, they have been sighted from British Columbia to Baja California, usually in the winter and spring months. This trend is reversed in North Atlantic areas. One of the bigger mysteries about the basking shark is that it is unknown where they go once they leave the coastal areas. It has been proposed that they may hibernate at the bottom of the ocean during non-feeding months, but this has not been tested. PSRF and other scientists are currently working to develop a sighting network and new tagging methods to help answer this question. RELATIONSHIP TO MAN The basking shark has supported harpoon and net fisheries throughout the North Atlantic for centuries. It was fished for its liver oil, which was burned in lamps until replaced by petroleum products. A single shark yields 200 - 400 gallons of oil. More recently this species has been used for fish meal and animal feed. In recent years it has also become a target for the finning industry, because of its extremely large fins. The fish are typically captured by harpooning, similar to the way that whales are fished. In some areas it is seen as a nuisance, because its habit of swimming on the surface causes it to become entangled in floating nets, to which it causes great damage in its efforts to escape. During the 1950's, eradication programs developed by the Canadian Fisheries Department annihilated populations of basking sharks along the coast of British Columbia. There are currently no reported commercial fisheries for basking sharks along the West coast of North America, but there have been recent confirmed reports of finned animals along the coast of California. REPRODUCTION Relatively little is known about the reproductive biology and behavior of basking sharks. The only report of a pregnant animal dates back to 1776! It is believed that they give birth to live young (they don't lay eggs), and the smallest juvenile measured about 65 inches in length. Females are believed to mature at about 13-16 ft. Basking sharks observed in the North Atlantic appear to breed in May. It is unknown where the females give birth. BEHAVIOR The study of the behavior of these animals is still in its infancy. Basking sharks have been observed breaching the water in great leaps, and also following each other head-to-tail. Most of those harpooned are female (30 females caught to every one male!), suggesting a possible separation of the sexes, either by time or location. The reasons as to why this is are unknown. CONSERVATION Observed numbers of basking sharks have been on the decline since the 1970's, and we believe have never fully recovered from the large scale commercial fisheries of the 1950's. Whether the declines are due to fishing pressures, some natural cycle, or simply that the animals are no longer frequenting the shallow coastal areas, is unclear. However, the basking shark is a slow-growing species that produces few young. Consequently, all substantial commercial fisheries developed for these animals have died out quickly as a result of over fishing. In California, while there may be no large scale commercial fisheries for basking sharks, several dead basking sharks have been discovered in recent years after the fins had been removed. Recreational boaters have been observed ramming and harassing the animals while they bask at the surface. PSRF has been working for the past 5 years to help develop legislation to assist in protecting this unique and interesting animal from over fishing and harassment. Moreover, there are organizations in the United Kingdom working to put the basking shark on the IUCN endangered species list, in order to help protect it from over fishing in the North Atlantic. We hope that with additional protections, we will see an increase in the numbers of these magnificent animals so that we will be better able to answer the many questions surrounding them. Basking shark, (8), in relation to other sharks...-1.jpg)

credit: Alessandro De Maddalena/Pelagic Shark Research Foundation |

| |

[ home ] | [ contact us ] | [ support us ] | [ shop ] | © Copyright 1990-2012 PSRF All rights reserved. |

Site Development by IT Director |